If you don’t get up in the morning early and write every morning, you don’t have those stray thoughts run through your mind, you don’t have them written down, they all disappear.

When we lose someone we love they are now forever with us wherever we are.

MH: It often seems to be a really good thing that we have a mother-daughter co-host team for many reasons, but one of them is that we seem to attract subjects where that’s a good fit, and today is certainly the case.

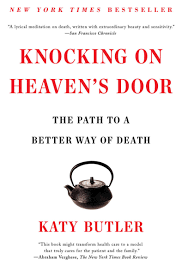

CK: It is. Our guest today is Katie Butler, and the book is “Knockin on Heaven’s Door: The Path to a

Better Way of Death.” It’s the most interesting book – one that everyone should read, they really should. It was most enlightening.

MH: It was eye opening for you?

CK: Well of course I had quite a bit of experience with this, with Ron, as far as that goes. Okay, she is a prolific writer and her articles have appeared in The New Yorker, The Best American Science Writing, The Best American Essays, and The Best Buddhist writing. Her piece for the New York Times Magazine, “What Broke my Father’s Heart” won the Science in Society award from the National Association of Science Writers. She lives in Northern California. This book is very personal from her standpoint and also very enlightening.

MH: Welcome to writer’s voices Katie

KB: Thank you. I’m very honored to be here.

MH: So you know I often ask our guests how they came to write this particular book and in your case the subject matter and then why you wrote this book really go hand in hand

KB: right yeah well I just want to step back and give sort of a little overview of what the book is about first so the readers have a sense of what we’re talking about. In essence the book is the story of my family’s journey through the last seven years or so of my parents lives. I was kind of a long-distance

caregiver for my parents I was flying back and forth across country a lot. They were living in Connecticut and I was living in California and essentially my father had a very long medically

prolonged dying that actually lasted six and a half years and my mother followed him fairly swiftly afterwards partly because of decisions she made she decided not to do anything to medically

prolong her dying and she died quite swiftly just before she turned 85 and the book is in essence it zigzags in-between me as both an observer and a caregiver for my parents watching this very painful stage of their lives and it zigzags between this very personal domestic story and a much bigger picture

which is essentially one of those sort of big issue questions which is how did we manage to transform dying into such a prolonged and for many people very excruciating process

MH: mmm

KB: So there’s a very personal family story but then there’s also the big picture story which is that three at least three-quarters of people say they want to die at home but actually only a quarter of people do die at home and a fifth of people die in intensive care which is an absolutely harrowing way of dying both for the family who survives as well as for the person who’s actually dying so that’s sort of the big picture so people have a feel for what the book is about.

MH: right

KB: and how I came to write it was you know I lived it and I had no idea at the time that I was living in that I would in fact end up writing about it. All I knew is that my life had just changed utterly

at the moment that I got a phone call from my mother who was a very stalwart, stoic woman, and I

got a call from her in this agony of tears saying that my father had had a major stroke and at that moment our whole lives changed and I became quite devoted and passionate about trying to help them and to ease their suffering. Frankly when it was happening, I felt like ‘this is taking away from my life as a writer.’ I wasn’t as productive. I wasn’t doing as much writing but I was living this very very intense personal story and I was keeping a journal the whole time.

MH: I wondered about that.

KB: When it was time to write about what happened I had all that precious raw material for the writer which is that, you know, if you don’t get up in the morning early and write every morning you know you don’t have those stray thoughts that run through your mind you don’t have them written down they all disappear and so I was very very fortunate I had all these journals.

CK: And you don’t have the facts of what happened when

KB: You don’t know what happened when and you see the vagaries of memory, and how you compress events and reverse their order and it was very interesting when I actually did write the book because I had to create these very detailed accurate chronologies and I was very surprised by how sometimes my memory differed

MH: Isn’t it funny how despite knowing that. we always think, when something’s happening, ‘I’m going to remember this exactly as it happens,’

KB: Right

MH: And yet we never do

KB: We never do I think we what happened sort of again a little bit of backstory here is that a year after my father had the stroke he was given a pacemaker in a very very rushed, in my opinion, very thoughtless way and this was at a point where my mother was pretty much an 18 hours day caregiver and my father couldn’t fasten his belt or really finish a sentence so they were both in a lot of misery and he got a device that really created a barrier to a natural death for him and I think helped prolong these very very last years of his and so that was kind of the journalist part of the story for me is that after these hurried decisions were made and I was looking back I went how did this happen here’s my father with a PhD my mother with a master’s bright people they had signed all those living wills and documents that you’re supposed to sign. They were pretty much in control of their lives they didn’t expect to lose control of their deaths

and yet we did and so I’d been already a journalist first you know 25 years or so at that point and so at some point my curiosity also got piqued and my passion, because I did see my parents go through a great deal of suffering that I later came to believe was not necessary and was actually created by medicine rather than eased bu medicine you know so I think the the two parts of me really got excited by the book and one part was how my own heart opened when I became a family caregiver and how we had a lot of Redemption emotionally as a family in those terrible years, and then the other part was the investigative reporters you know the baby boom ‘question authority’ part of me which said ‘hey wait a minute how did we get here?’ and I just really couldn’t rest until I at least figured out a scheme for it that made sense to me

CK: Well my question is, if they had living wills why weren’t they honored I mean I thought the whole point of a living will is to

KB: They were honored. The problem is we see death and dying as an event and I’ve come to believe that death and dying are really a pathway, if that makes any sense. It’s like my father’s dying really took place over six and a half years

CK: mm-hmm

KB: So at the point where he got the pacemaker he wasn’t dying, you see?

CK: oh I see

KB: I mean I knew that he was on the pathway to his death but he was actually years away from actually dying and so we didn’t think of this as a living will situation it wasn’t like showing up at the door of the emergency room in a panic with an 88 year old who’s having trouble breathing right? This was a guy who was still walking around getting his own breakfast but we have invented these advanced medical technologies and so the pacemaker had a 10 year battery and it was put in my father when he was 80 and really couldn’t speak

MH: hmm

KB: and nobody thinks at that point of having a detailed conversation where you say hey wait a minute let’s slow this decision down this device has a 10 year battery. It’s gonna take away from this man one of the most merciful and peaceful ways that he could die such as just simply dying in his sleep, simply dying because his heart stopped. We need to have a very deep conversation with the family now about the long-term implications of this you know

MH: yeah

KB: Unfortunately I mean signing living wills is a wonderful thing to do and we all ought to do it

but it’s really only a first step because there’s a lot of emotional and I believe moral or spiritual work that also needs to be done around the same time where you you’ve made peace with your family you’ve said your apology’s and you’ve given your blessings even though your death may be

three or four years away, you know?

MH and CK: yeah mm-hmm

MH: I have a friend who not long ago had a family member who had had several strokes and on the

last one this friend of mine was ready to make the decision not to put in the feeding tube because one doctor was saying you know your loved one is it’ll be unlikely that they will ever even be able to get from the bed to the chair, they’ll never be able to speak coherently, they’re never going to get any better and she was ready to make that decision but then there were people in the room like a nurse saying oh you have to do it you have to do it you have to give her a feeding tube

KB: You don’t.

CK: Well you know Grandma

MH: yeah

CK: My mother had several small strokes, could not speak and then she couldn’t eat, couldn’t swallow ,and she had she had written a letter saying that she – it was not an official living will in a document but it was a letter – saying that she didn’t want any extraordinary things done and I told the doctor that and he said ‘well then that’s it.’ He didn’t argue with me at all. I’m very grateful.

KB: It’s so wonderful that you two are a mother and daughter doing this interview you know because I think these are decisions we often have to make with one or two generations and usually the women are the ones are the caregivers and making the decisions. I think it’s very important to know that legally there is no requirement – you have the legal right, the constitutional right, literally (it’s a Supreme Court decision) to refuse any medical treatment and to ask for the withdrawal of any medical treatment so you can do that for yourself and you can also do that obviously if you are what they call the medical proxy or the medical surrogate – you’re the decision-maker for someone who can no longer articulate their own decisions – so it’s very important to know that neither morally nor legally is there any requirement to accept a feeding tube for example or a pacemaker. You have the absolute right to request if someone has an internalized defibrillator, which gives you a terrible shock to

restart your heart, you can ask for that to be turned off and in fact it’s very important that it gets turned

off on the deathbed because it can fire repeatedly causing extra pain so it’s important to know this but unfortunately it’s the luck of the draw at the moment as to which doctor or nurse you run into based on their personal beliefs and philosophies okay?

CK: that’s true

KB: So I think it’s very important when you get into these feeding tube discussions especially to

ask for the involvement of the palliative care program hospitals now have specialists who are called

palliative care specialists and they are much more attuned to quality of life than quantity of life and they can be very very helpful in kind of running interference in a hospital if you feel like your wishes and the wishes that the family member are not being followed and the doctors or nurses are trying to

impose their own particular moral values.

MH: Aren’t there even situations where doctors have gone to court to try and force their decision over the family members?

KB: Yes and the main decisions the families have won. The most major one was actually a long time ago, it was 1989, and was a very devout Catholic family who asked for the withdrawal of the respirator and I believe also a feeding tube from a woman who was completely in agony and unconscious both at the same time and the Supreme Court said you have the right to refuse any medical treatment or ask for its withdrawal and then there’s nothing in the law that says you’re required to make the people you love suffer on their way to death and I think there’s very important concepts such as there’s life and then there’s meaningful life, right? There’s life and there’s sort of the pure idea of simply keeping a body breathing versus the idea of what is a meaningful life for that person and you know, people

are all across the spectrum on this and some people are willing to put up with a lot of pain for an additional month or two of life and others really really don’t. There’s a very interesting study to me which showed that 28% of people with congestive heart failure, which is very sort of painful where your heart just can’t pump enough blood to you – twenty-eight percent said they would trade a single day of excellent health for two more years in their current conditions so there’s at least a third of people who really opt for not overly extending the suffering of the end of life. But another very important point is, there’s a phrase that hospitals use called the “nephew from Peoria” and the nephew from

Peoria is the family member who’s somewhat estranged who flies in from a long distance away and insists that everything be done.

MH: hmm

KB: And often the hospital will be intimidated because they’re afraid that that person will sue

CK: right

KB: So even if you have a living will and you signed all the documents and you’ve appointed someone totally different to be your medical decision maker you really have to watch out for those estranged or distant family members again I think this is where I come back to this is not just a legal paper problem it’s an emotional family problem. And the work of signing your documents, of doing your living will is

not simply to sign those papers in the doctor’s office all by yourself, it’s to make sure that you have all your family members on board including maybe that you know half-estranged one that lives 3,000 miles away and rarely talks to you.

CK: The one from Peoria.

KB: Right. You really need to have a heart-to-heart conversation with them and ask them for their commitment to do what you need and not what their emotions are driving them toward.

CK: mm-hmm that’s a good point

MH: Katie let’s talk a little bit more about the writing of the book. You said you had your journals from this time period. You also had some journals from your mother didn’t you?

KB: Yes I did. I was really gifted and graced in that my mother, before she died, sent me photocopies of some pages from her journal and then after she died I had her whole journal as well as all of …

my father was a historian so they saved every little letter and postcard that they ever wrote or received. You know, there’s just piles. And as a journalist, it couldn’t be better!

MH: Now, have you made your way entirely through that archive yet?

KB: No, I haven’t. There’s like two boxes in the garage. I’ve gone through the ones that are really

important to me. It’s so fascinating – because I’m a writer my journals are very sloppy and very verbose. I use those Mead spiral-bound notebooks, you know college bound notebooks that you get at the five-and-dime, right? And I just I do a lot of free writing. I like to get up early and just let the pen travel fast and see where it takes me, so there’s a lot of dross in my writing. My first, my “super-first” draft, my “pre-first” draft. But my mother was just the opposite. She was an artist and a minimalist and so her journal is only probably 20 pages or so but it is so concise and so direct and so moving as a result.

MH: Did your mother know that you were writing this book?

KB: She knew that I was writing an article for the New York Times which preceded this book but she actually died before the New York Times piece was finished and so she didn’t know about the book itself, but she was very supportive of the New York Times article which was really something for

her because she was of an older generation that is much more tight-lipped emotionally; doesn’t share publicly, you know?

MH: Right, right, and one thing about this book is it is almost as much about your relationship with your mother as it is about your father’s death, going clear back to early childhood and I’m wondering – I guess I the question is why you decided to be so open and honest about that part of the

family relationship.

KB: We had a difficult relationship, you know she was an uber housewife and I was the most terrible housewife in the world and I was a journalist, right? So there were some inherent ways that we rubbed each other the wrong way and I think that goes back a long, long way. We came to quite a bit of redemption, although very imperfectly, in these last eight years where I did step up and really help them. I wrote about it so openly because I know this is a very very tough life passage for everybody, you know, for the for the aging parents and for the daughters and daughters-in-law and sons who are helping. I wanted to make sure that everybody – I didn’t want to come across as a saint. I mean nobody in our family was saintly. I wanted the reader to understand that they were not alone and if they had horrible scenes with these parents that they were trying to help that this was absolutely normal and that lots and lots of families go through some version of this. I sort of feel like one of the under themes of the book is that I came to be much more openly expressive of my love to everybody as a result of what I went through with my parents, and a lot of that had to do with working some things through with my mother because she was very critical, very perfectionistic, and and I was frankly scared of her for much of my life, and I inherited some of that perfectionism.

MH: mmm

KB: Sort of like – well if life isn’t perfect or people aren’t perfect I’m just going to hold back. And I think what I learned from this whole life passage was: don’t hold back. Express your love for people, in word, and in deed, and accept your own imperfection and accept their imperfection and love everybody including yourself anyway. So that’s why I was so open.

CK: You know what you said about showing people that it happens in every family, in every life – that is extremely important because one of the big stumbling blocks to people’s happiness and contentment is thinking they are alone in this situation

KB: Yes.

CK: And there’s nobody else that’s feeling this way, has never felt this way and then when you find out, oh yes there are other people and you know, that’s monumental as far as I’m concerned.

KB: Thank you. Right now, there are like 24 million Baby Boom caregivers that are helping aging parents. And so many of us are facing some version of this decision that we faced with my dad because eventually my mother and I asked to have the pacemaker turned off so that he could die a natural death, and we didn’t succeed, but that was a harrowing experience and because of these advanced medical

technologies, just as you were saying about your friend and the feeding tube, there’s a panoply of devices that we have to address on a moral level and I think this is one of the hardest things I ever did in my life. And again, I don’t I don’t want people to think they’re alone facing this.

CK: Right

MH: And one of the things that makes that decision so difficult is that there’s always hope that the person will get better if you just give them a chance.

KB: Yeah. And sometimes that’s the case. That’s what makes it even worse.

MH: mm-hmm

KB: I like to talk to people about – I call it Humpty Dumpty Syndrome – I think that when you get into your 80s and 90s a lot of people are like Humpty Dumpty. They look actually pretty good on the outside but it really doesn’t take much to knock them off the wall and you can’t put them back together again. And I’ve just seen this over and over again now because I’ve written the book, I which I’m going to just say is “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” because I know we have a long show and if people are just tuning in I want them to know. I see someone in their 80s or 90s given open-heart surgery or colon cancer surgery, a major major surgery, and they simply can’t bounce back and as a result they do die in intensive care with this sort of huge technological flail going on. When actually if you had just wound back to clock it was really time for a responsible doctor to say ‘your mom or your dad is approaching the end of their lives. We could do this surgery for colon cancer but my fear is they will not

survive it and it might be better if we start to face the approach of death on an emotional and spiritual level now instead of trying to deal with this is a medical problem.’

MH: mm-hmm

CK: That’s a conundrum for doctors too isn’t it

KB: It is. It is. We put them in an impossible position. because how are they supposed to

predict perfectly what’s going to happen.

MH: Well they can’t.

KB: They can’t.

CK: No.

KB: They can’t and sometimes we expect them to.

CK: Right. That’s exactly right.

KB: With my mother’s death, because she refused open heart surgery at 84 and she died five months later, but the way I think of it now is we all die too soon or too late. Nobody times it perfectly. Seriously!

MH: You’re right, you’re right

KB: We’re too logical, we think we’re gonna be able to make it all just come out just perfect and it’s kind of like going to the airport. Things do not happen just the way you want them to and

because my mother was willing to die too soon rather than too late she actually had a very good death according to the way she wanted to die.

MH: Wow

KB: You know, if she’d had that surgery she might have gotten an extra three years. Then again she could have come out of that surgery extremely demented because there’s a high risk of dementia with open heart surgery. And stroke. She didn’t want to take that risk and I had to respect her for that.

MH: Yeah and in fact if I were you I might have felt grateful to her for that.

KB: You know I do and I don’t. It is always hard when someone dies too soon.

MH yeah

CK: yeah

KB: As I said, there’s like very few perfect endings and I certainly wished I had had a little more time with her but it was her death and it was really her. And in retrospect I am incredibly grateful that I did not have to become her caregiver the way she and I were my father’s caregiver; that I didn’t have to go through another five years of this. Of course I’m grateful.

CK: Well yes and you didn’t have to watch her suffer. You didn’t have to watch her slowly die.

KB: Yes, because we had done that for six and a half years with my dad.

MH: Now Katie you mentioned that usually it’s the daughters and daughter-in-laws that provide the bulk of the care and it does seem like your brothers, you have two brothers who didn’t participate nearly to the extent that you did during this time period. How did this whole experience impact your

relationship with your brothers?

KB: Wow. Well I, you know I hate to say it did. I, first of all just have to say, I love my brothers and there were very good practical reasons why it was much harder for them to step up and do what I did. I had a much more flexible job, I had more money, you know there were just a number of things I had going for me that they did not. I’m very close to one of my brothers still and during that whole time he was an amazing emotional support for me even though he wasn’t that involved with my parents so I got to call him and vent a lot and he really helped me feel not alone.

CK: mm-hm

KB: The other brother, sadly, was semi-estranged from most of the family before this happened and is still semi-estranged from my other brother and me now, and I certainly think, you know, the cracks that already exist in a family don’t always get redeemed in crisis and stress, in fact they sometimes get worse. And so I guess I would have to say that about my relationship with my other brother, which is it’s sad, but again I’m not the first family to go through some version of this.

MH: Did you get any reaction from your brothers to this book?

KB: Well the funny thing is, as I said, one brother’s semi estranged so I really have no idea. The other brother is very, very proud of me and proud of the book but he is a long-distance truck driver so he really doesn’t have a lot of free time. And I do in fact have a series – the book is on CD now. “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” is on CD as well as hardcover and Kindle, and so I’m hoping that at some point he’ll be able to listen to CDs on the truck and then he’ll be able to listen to this. But actually he’s already listened to a lot of the book because while I was writing it I and he was driving truck I would call him and read him whole chapters aloud so he’s probably probably heard as much as he needs to! He was very helpful too. He’s a very good editor, you know very good at summing things up and sort of

feeding it back to me in a condensed form.

MH: Well one of the things when you’re writing nonfiction about family members, you know, it can be very, I think, difficult to decide what to put in, what to leave out. You don’t want to hurt somebody. It probably was a little bit easier here because the the most important characters in this story are both gone.

KB: yeah yeah

MH: Could you have written it while..

KB: I couldn’t have written it while they were alive.

MH: That would have been probably more difficult. Was it emotional for you to relive all

of this by writing it?

KB: Yeah it was and there were times that I was writing through tears and it was also very healing

It was very healing because – I don’t know – even the tears are healing because it makes you realize how much you love those people and how beautiful some things were. It was very healing. Toward the end of the book I write about feeling that I had really let my mother down in the last year of her life. It was partly that I was exhausted by my father’s death and whatever else. I was in denial and, you know, my relationship with my mother was complicated but I had to actually just write in the book, you know, I let her down and now it is too late. And again in a way that’s healing for me to simply just put that on paper and again for the reader you just don’t know what reader is gonna read that and go, ‘oh, you

know I still have another year with my mother. I’m gonna make peace with her. I’m going to deal with our conflicts. I’m gonna fly back there.’

CK mm-hmm

MH Yeah

KB So you hope somebody benefits from your mistakes as well as from what you did right.

MH: I expect that will be the case.

KB: I think so. I mean from the letters I’m getting from people it already is the case. They’re having

conversations in their family that they haven’t known how to approach and that just really really is very warming to my heart. It’s wonderful.

MH: You’re listening to Writers voices with Monica and Caroline and our guest today is Katy Butler, the author of Knocking on Heaven’s Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death. Katy, I

understand your book has actually gotten quite a bit of attention since it came out.

KB: That’s right. It’s on the New York Times science bestseller list. It’s been on several local bestseller lists like San Francisco regional, you know, and I think Minneapolis and Denver and it

was named one of the hundred best books of the year by Publishers Weekly just a couple days ago.

MH: Wow congratulations.

CK: I’ll say.

KB: One of the 10 best memoirs of the year, I mean, and an editor’s pick from the New York Times and so… It was a kind of a risky book to do because first of all it’s got death in the title and there’s the fear that no reader is gonna pick up a book about death. And then I’m a first-time author and on top of being a first-time author, I’m a first-time author of 64, so in a lot of ways. I mean I had a wonderful – Scribner as my publisher – an absolutely wonderful publishing house so I had a lot of support but there were some real strikes against this book just going in. So in my opinion it just shows how desperate we are as a culture to have a more meaningful and realistic conversation about dying.

MH: Absolutely. Once I started reading this book I knew that it would be a best-seller., to tell you the truth.

CK: Yeah.

KB: I love it!

CK: I was going to ask you why why the tea kettle on the cover and then I remembered your mother served tea every day, positively.

KB: That’s right. And the opening scene of the book, which is a scene that I really did struggle over for quite some time, is the scene where she is serving me tea from a teapot very much like the one that’s on the cover.

CK: mm-hmm

KB: And she says to me, ‘please help me get your father’s pacemaker turned off,’ and that was one of those life turning points.

CK: Right

KB: And I struggled over how to write that scene and where to place that scene from before I even know it was going to be a book, and whether that was too risky a place to start the book, or to start the article that preceded the book, so the kettle is very meaningful to me and I think if you read the book you see it. I’m not sure if you’re just picking up the book you’ll see it, you know.

MH: Katie how did you find your publisher?

KB: Well it was one of those sort of overnight successes at 64. You know, essentially, when I was deep

into this horrible situation where my mother and I were trying to get the pacemaker turned off and failing, and I suddenly was so amazed by how did we become so disempowered in the face of

medicine? I really couldn’t rest until I got this published, so I published a piece in The New York Times Magazine, which was a leap for me. I had already written for The New York Times science section but writing for the magazine is much more complex and difficult and hard to get into. So they accepted the article. They published it on Father’s Day 2010, and they didn’t push it really heavily. It was sort of buried below the fold, you know, it wasn’t promoted heavily. And it just shot to the top of the most emailed list. Everybody was reading it. They were sending it to each other. They were commenting. There were over 1200 comments all together, either to the New York Times, or to me, my personal email, and so it became kind of a sensation in New York and also in cardiology because it

was such a challenge to cardiology.

MH: hmm

KB: I was overwhelmed actually. I was getting all these letters and emails from people talking about their agonizing experiences with the medical system at the end of life.I actually emailed another writer that I knew and said, ‘how do you handle this emotionally?’ Because it was just

overwhelming and he emailed me back and we emailed back and forth and then he said, ‘Well, by the way, my literary agent in New York is this woman named Amanda “Binky” Urban and if you’d like her to be your agent, I would love to suggest you to her,’ and I said ‘please do.’ and so… Binky Urban is this sort of tough love agent, you know, very, very tough New York agent who represents people like Mary Karr, Tobias Wolff and numerous real literary lights and so I said ‘well yeah, of course!’ so he put me in touch with her. Long story short, after the agony of producing a book proposal, you know, she showed the book proposal to people she thought it would be who would be interested in I was very very lucky that Matt Graham at Scribner got excited by the book.

MH: Katy, when you did the article for the New York Times Magazine did you write that on

spec or did you pitch it first?

KB: Yeah. I pitched it. So I pitched it but I was known, in the sense that I’d already written smaller pieces, which is what I encourage all other writers to do is like you know wherever you are try going

up one rung you know it’s like if you’re writing 400 piece word pieces for your local paper try something that’s a thousand words long for a slightly bigger market and that’s really what I

did over the course of 25 years or so. So I got the name of an editor from a friend of mine who’d written for that for the magazine before and I pitched her. I actually pitched the New York Times twice First time they turned me down but a year later they said yes. First, I went to a Writers Conference that was supposed to bring East Coast editors together with West Coast writers and you could have a little 15-minute pitch session with one of their editors and I did that and but it was sort of too early on

then in on the process. I think my father was still alive and I really hadn’t sorted out how to pitch that story to the New York Times.

MH: hmm

KB: So I got turned down. You know it was too vague at that point. I didn’t understand that you have to be able to write why is this an important story for your particular readership and why is this an

important story for you to tell now. As someone once said to me, a really good magazine story or book has three elements. A – it’s a very good story in and of itself. It’s interesting. The characters, the plot are interesting, and B – it says something about a trend or it says something about this particular time in history. and then C – it says something about the eternal human condition. If you have all those three elements, you really have a chance of writing a very good magazine piece or a very good book that people will really want to read, okay? And so in this case we had the personal family story here. You have a mother and a daughter struggling with each other and wrestling with this terrible moral decision of what do we do? Do we let this person we love, die a natural death? Do we fight for that or do we just let there be medicine as usual? So we had an interesting plot, and then on the second level this is a very significant social story because it’s not just about our family. Because of all these medical devices like.. in everything from CPR, to 911, to dialysis; all of these things present these terrible moral choices, so we have something that’s very particular to our society now. Then finally, you know, the fear of death, the struggle to face death, the spiritual opportunities and the emotional opportunities that death presents us if we can face it – I mean these are really eternal. Things we’ve been struggling with, spiritually and culturally probably – well you know – go back to the caves. You have you know funeral ceremonies and you know

MH: Absolutely, yeah. I don’t think there’s any topic that’s much more eternal.

KB: There isn’t anything more eternal than dying (chuckles)

MH: Exactly

KB: Do you want me to read anything from the book, or do you want to keep talking? I mean I’m fine either way, whatever you’d like.

MH: Why don’t you go ahead and read from Knocking on Heaven’s Door?

KB: Okay I’ve got a choice for you. I can read from the beginning, which is about these terrible moral moral dilemmas, or I can read about my mother’s death which I think is very encouraging in a way. Which do you prefer?

CK: The latter I think

KB: ]Ookay okay. So I’ll just set it up for you here. This is from a chapter called “Valerie makes up her mind.” My mother’s name was Valerie and when we discovered she needed open-heart surgery

I took her to Brigham Women’s Hospital in Boston in a terrible rainstorm. This was like the best place I

could find for heart surgeries for the very old because she was already 84 at this point. We went in. We sat in this windowless room. The surgeon came in and said “what are you here for?” and my mother said “to ask questions.” I’m gonna read a little bit from the book here and then I’m gonna skip a bit and read about the end of her life.

She was no longer a trusting and deferential patient. Like me, she no longer saw doctors as her healers or her fiduciaries. They were skilled technicians with their own agendas, but I couldn’t help feeling that something precious: our old faith in a doctors calling perhaps, or in a healing that is more than a financial transaction or a reflexive fixing of broken parts, had been lost. The surgeon told us that my mother’s age was not a barrier.

KB: Now she was 64, sorry she was 84, at the time and he told her that she could live to be 90 if she had the surgery and that if she didn’t have the surgery she had a 50/50

chance of dying within two years. He also admitted that there was a major risk of stroke or dementia and then he sent her off for another test and I went into the waiting room and I called my brother Jonathan on the phone and said I was really petrified that she was going to have the surgery and come out badl. And she came back from this other test and she put on her coat and she said to me ‘No I will not do it.” Okay so now I’m going to return to reading from the book again.

My mother spent her last spring and summer arranging house repairs, thinning out my father’s bookcases and throwing out the files he’d collected for the book he never finished writing, saving

only the love letters he’d written her when they were in their 60s. She told someone she didn’t want to leave a mess for her kids. Her chest pain worsened and her breathlessness grew severe. “I’m aching to garden; to tidy up the neglect of my major achievement,” she wrote. “Without it the place would be so ordinary and dull, but so it goes – accept, accept, accept.”

My mother’s heart nurse called me, urging me to get my mother to reconsider surgery. My mother was so healthy in other ways, the nurse said. Uneasy, I called Dr. fails (who was her internist.) I know your mother well enough and I respect her he said. She doesn’t want to risk a surgery that would leave her debilitated or bound for a nursing home. I think I would make the same decision if it was my mom. I called my mother and said “Are you sure? The surgeon said you could live to be 90.”

“I don’t want to live to be 90,” she said.

“ I’m going to miss you,” I said, weeping. “You’re not only my mother, you are my friend.”

That August she had a heart attack. She was still in the hospital, in a step-down unit, when I got a call from yet another member of Middlesex Cardiology Associates who’d been handed my mother’s case. The desire of doctors not to give up on my mother, to resist death and to show their caring by doing something, anything, seemed unstoppable.

The doctors were considering giving my mother coronary artery bypass grafts plus the two valve replacement surgeries she rejected when she had a far better chance of surviving them in decent shape.

She seemed to be heading down the greased shoot toward a series of Hail Mary surgeries; risky, painful, dangerous and harrowing; each one increasing the risk that her death, when it came, would

take place in intensive care.

Burning with anger, I told the astonished cardiologist that my mother had rejected surgery before her heart attack and I saw no reason to subject her to it now. I called her in her hospital bed.

“I think we’re grasping…” I stopped.

“At straws.” she said, finishing my sentence.

It was quiet. ‘It’s hard,” she said “to give up hope.”

Four hours later she called me back. “I want you to give my sewing machine to a woman who really sews,” she said. “It’s a Bernina. They don’t make them like this anymore. It’s all metal, no plastic parts.”

“But I’d like it,” I said.

“But Katy,” she said. ‘You don’t sew. I’m ready to die,” she said. “I’m at peace with all my children.”

She was overflowing. She told me she’d found the little spiral bound notebook I made for her eightieth birthday. “It was so loving,” she said, “and oh Katy, I didn’t appreciate it. Cherish Bryan,” she went on.

“You mean stop being a snob and cherish Bryan?” I asked (he’s my partner.”).

“That’s exactly what I mean. I love Bryan.” she said. “I love Bryan for what he’s done for you.”

An old Zen master once wrote:

Old plum tree

bent and gnarled

all at once opens one blossom, two blossoms, three four five blossoms

uncountable blossoms

whirling changing into wind wild rain, falling snow

all over the earth.

My mother was like that.

KB: I could stop there or I can go on. do you want me to?

MH: that’s a good place to stop

KB: Okay and then I just want to sort of fill you in, which is that you know months later she had a second heart attack. She was on Hospice at that point and she was taken to a in-the-hospital hospice unit. She had hammered silver earrings that she wore day and night for years and she said “I want to take off my earrings,” and the hospice nurse said “You don’t have to take off your earrings. This is a hospice unit, you can wear whatever you want in the hospice unit,” and she said “I want to get rid of all the garbage,” and I think that was her way of saying ‘naked I came into this world and naked I will

return’ and she sent my brother off to call my other brother and me and 20 minutes later she was dead and you know, like all deaths, it wasn’t perfect…

MH: No but she went on her own terms

50:00

KB: Exactly. It was also an absolutely beautiful and brave death that she faced in a very old-fashioned way – very head-on – and it allowed her, it gave her the time you know to make peace with me, to make peace with my other brother, to express this extraordinary outpouring of love and blessings that she, you know. There’s a wonderful way that when you know you’re dying, you, it’s kind of all bets are off and you can say anything. In ways that were very healing for all of us and I’m sure for her too.

MH: Oh yes. So for someone who just tuned in, that was Katy Butler reading from “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” a few minutes ago. So Katy, when you started writing the book. was it a full-time occupation for you?

KB: Yes absolutely. I was lucky enough to get a very good healthy advance so that I was really given plenty of money to write the book and do nothing else and that’s what I did.

MH: And how long did it take?

KB: I’d get up at five in the morning because I share a house with Bryan and my, you know, my in- home office is right off our kitchen, so I found that the only way to really get a productive work day in before I was distracted was to get up at five and write of and on until about ten or so, and definitely to quit by noon.

MH: mmm

KB: Then I’d take a hike with friends in the afternoon and you know do the grocery shopping and everything else but that I really needed those absolutely silent uninterrupted hours in the early morning.

MH: Do you do all your writing on computer or do you do some by hand?

KB: No, I do a lot of first draft writing by hand in these Mead notebooks. I find, I really believe it actually changes your brain; that writing by hand, at least for me, allows me to access a more informal and emotional and spiritual part of myself than writing on a computer. You know, like the computer says “work” to me, you know? If I’m upstairs – I have a little teeny sort of sub-bedroom upstairs, a little study, and I like to write my first drafts by hand up there looking out at this beautiful willow tree and then I go back later with a yellow marker and highlight the things that are worth saving.

MH: When you put that part into the computer is there still a lot of editing after that?

KB: You bet. This book went through three major edits. I submitted early a very, very disorganized first draft. I got a lot of help from my editors at Scribner about where to move things around. I then rewrote it and dropped a lot of stuff but it was still – the second draft was still, I’d say somewhat self-indulgent, you know like was in love with the sound of my own voice. It was slow, it wasn’t tight enough. It wasn’t direct enough in certain places and so then I scrambled to do a third draft right before it was really due. I mean I’m like that. They say you know the the trip to the guillotine and the tumbril clarifies the mind. You know it’s only when I have like this absolutely drop-dead deadline that the adrenaline courses through my brain and I get braver, more direct. And they actually had me add the two chapters at the end which are much more kind of how-to-do-it chapters. They’re very very direct advice on how to approach the end of life and with a lot of resources and, you know, kind of more like a manual almost and those were written in the last month or so of the book. Again I had to sort of access that prophetic voice, you know, which is sort of like ‘this is what I learned in seven years of caregiving. This is what I learned and I’m going to tell you about it very directly. That’s a very different voice from the rest of the book because I wanted the book to read like a novel. you know. I wanted you to be in love with the characters and interested in what they wanted and how they were in conflict and

how they reconcile. I wanted you to be fascinated and I didn’t want to hammer anybody over the head with the polemic or the political part of the book.

MH: Right, and I think that was a good choice to pull that part out.

KB: Yeah and thank you. It’s a real shift in voice.

MH; Yeah. So you have a real narrative flow through the rest of the book and the overarching structure is basically chronological but you have a lot of flashbacks to earlier times. Is that something that’s hard to do to do, those transitions to the flashbacks back and forth?

KB: Yeah. Frankly there’s one chapter where I don’t think I succeeded, unfortunately. If I had my

fourth draft, which would be my druthers, I would make it even more chronological than it is now and I would pull out some of the flashbacks so that it wasn’t confusing. Someone once said to me a confused

reader is an angry reader and I think it’s true.

CK: yeah I think so.

KB: I teach at Esalen Institute in Big Sur and I always say to my students, “There are three questions you can ask your readers,” because as I said I really love to read stuff out loud to, you know, willing listeners, but I always ask them three questions which is: Where were you bored? Where were you fascinated? And where were you confused?

CK: mmm-hmm

KB: I think that’s much more helpful than…

MH: What did you like?

KB: Yeah it’s much more useful than ‘what did you like?’ or ‘what did you think was good? or ‘how do you think I ought to rewrite this?’ If you have those three pieces of information you can really work on your next draft with a lot of direction.

MH: That is very, very good advice for writers.

CK: It is.

MH: So we only have a minute left. Tell us what you’re working on now.

KB: Getting my life back! I’m involved in this massive continuing promotion of the book so I’m speaking at hospice programs, and I am now speaking at what they call Grand Rounds where you actually go into hospitals and speak to their cardiology professors and cardiology rooms. So I’m, more than anything frankly, I’m missing writing. I do have a big investigative story that I’m hoping to do next which I can’t really reveal, but it’s also a medical device story. But frankly I’ve really become a public speaker and I’m really hoping to influence how we deal with the end-of-life, because it’s a two-way problem. There’s a problem within medicine and then there’s a problem within us because we can’t face it.

MH: Well I think you’ve definitely taken a big first step with ‘Knocking on Heaven’s Door’ in being influential.

KB: Thank you

CK: I would say so, yes.

MH: Because it’s a very important book.

CK; It is, as I said.

KB: Thank you, I really enjoyed this.

MH: And I hope we get to talk to you again with your next book.

KB: Yes, and tell all your listeners to keep writing.

MH: Absolutely.

CK: Yeah that’s what we do. I want I want to share this with with her.

MH: Okay

CK: This is St. John Chrysostom said this. ‘When we lose someone we love they are now forever with us, wherever we are.’

MH: See you all next week on writers voices

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS

Want to join the discussion?

Feel free to contribute!